Purely by accident — a dichotomy at the box office has people flocking to theaters in numbers that are probably making Tom Cruise frustratingly aroused. Why in the world has the double feature of Greta Gerwig’s Barbie and Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer driven more people to movie theaters than we thought possible post-COVID?

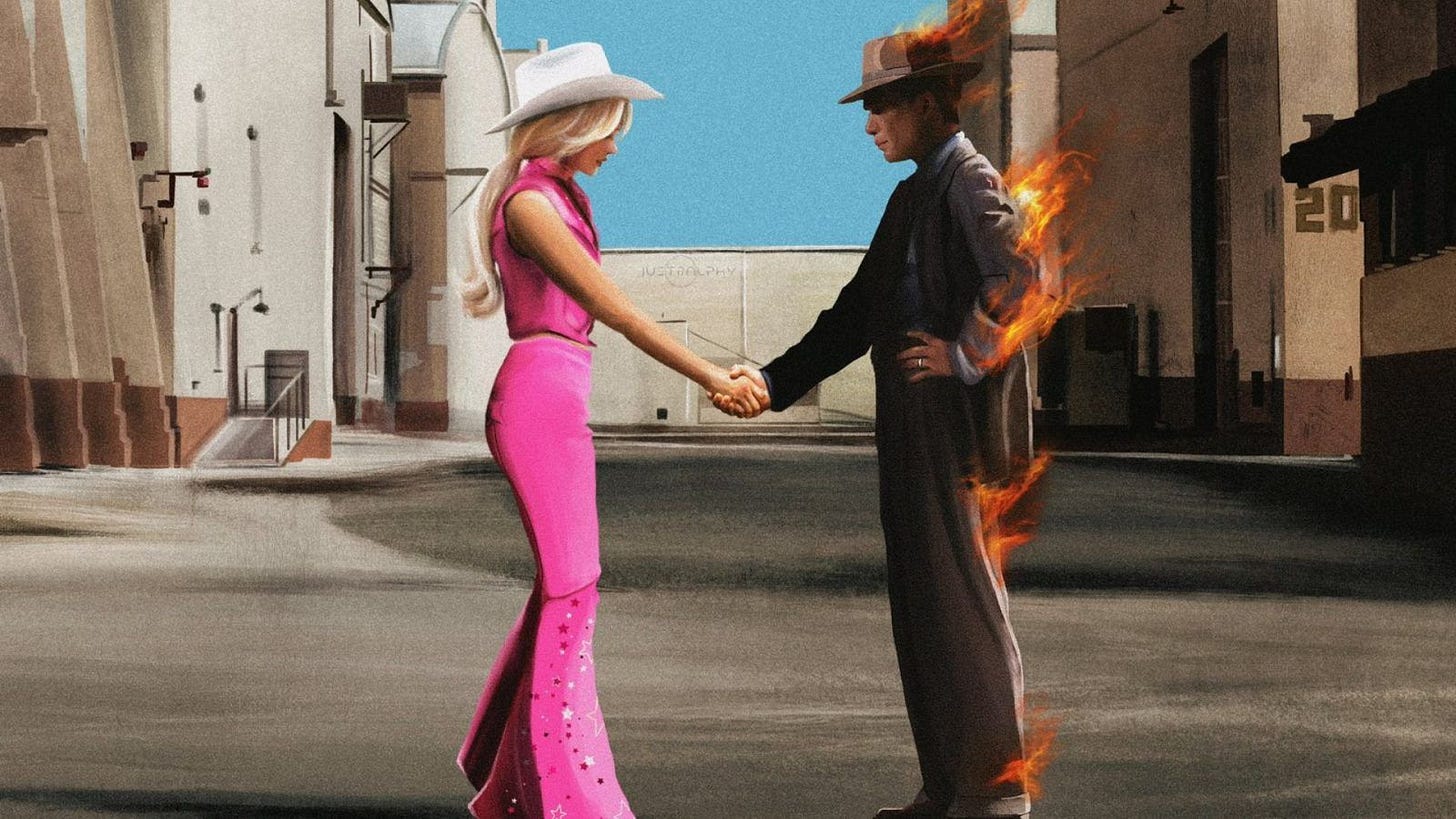

Pictured: Barbie and J. Robert Oppenheimer Agree Not To Cannibalize Each Other’s Box Office Total in One of History’s Great Joint Slays…

I don’t really know, but there can be little doubt that their shared release date helped bolster and magnify the theatrical experience of the other.

In theory, these films should have such different audiences — and moreover, both are major releases from popular renowned directors — that surely any association between the two would boil down to one group prioritizing the viewing of one film over the other.

At least, that’s how marketing movies traditionally works.

But in an unprecedented (and surely unreplicable) internet-fostered phenomenon, the nation caught onto the bit: these movies are so tonally different, wouldn’t it be funny if we all dressed up and saw both?

Any way you spin it, this past weekend has been a celebration of movies. And it’s been a joy to partake in the fun myself…

Considering Oppenheimer…

Peeing with my Fellow Kens…

Worrying About The Ramifications of My Creation (This Substack)…

But amidst all the fun, it’s easy to get swept up in whether or not these movies deserve the wave of love they have received.

Overall, I would like to offer my wholehearted endorsement of both pictures — with the caveat that neither are without flaw. But isn’t it the presence of those flaws what has made the BarbenHeimer movement so exciting?

I’ll begin with Barbie: I had a really great experience both times I saw this film. The first hour is significantly better than the final act, but overall the movie delivers on exactly the kind of sardonic tone that I believe it’s audience was looking for.

Where I believe the film stumbles, is in it’s sudden insistence on it’s own poignancy. I cannot stress enough how much I support a tonal shift in a silly movie. It is overwhelmingly possible to balance cynicism and heart.

I did not find, however that Barbie was successful in that regard.

The more explicit, the less effective the criticism

As I said previously, the first hour or so of Barbie provides biting sardonic jokes about the state of real-life femininity. The crux of the laughs that come so organically as we are introduced to Barbieland, is that women (the Barbies) are unambiguously in charge of their lives, and the men (the Ken’s) are accessories.

There is no Ken. There is just Barbie and Ken.

Traditionally, if there are two attractive movie stars as magnetic as Margot Robbie and Ryan Gosling, the audience expectation is that they will get together in some capacity. This movie does an excellent job at mining laughs from exactly how meaningless Ken is to Barbie. Gosling absolutely thrives in the role, cementing his status as one of very few movie stars left who can adeptly subvert their good looks and charm.

Barbie started to lose me once Barbie and Ken arrived in the real world. There, the movie loses it’s grasp on what makes the satire work, and starts relying on extremely broad notions of female empowerment.

One of the weakest jokes in the movie — which effectively sums up this misstep — comes when Barbie meets the male CEO (Will Ferrell) and all-male board of the Mattel corporation.

Barbie asks to meet their CEO, to which Ferrell replies, “That’s Me,” and quickly launches into a defensive diatribe about how Mattel had a female CEO in the 90’s.

This movie begins with such a firm grasp on the satirical thrust of its feminism, and then quickly loses itself in the tired trope of feminism-is-when-woman-runs-the-terrible-corporation-and-exploits-workers-as-well-men.

Barbie returns to Barbieland shortly after, only to find that Ken — who has learned the ways of patriarchy from the real world — has turned Barbieland into the Kendom. Crucially, what makes this section of the movie effective, funny, and keenly cynical is the comical subjugation of the Barbies in the Kendom.

In Barbieland men are not subjugated, they are simply irrelevant. But when the Ken’s take over, the Barbies are debased, over-sexualized, and turned into second-class citizens. The ludicrousness of this situation, is a point well taken — it’s only when the film makes its intention’s more explicit that the seams start to show.

After the Barbies return Barbieland to its former glory, Robbie’s Barbie isn’t sure she’s ready to resume the status quo. Instead, she chooses to become human, leading to a bewildering, visually uninspired, (especially for such a wonderfully designed picture) broad, montage of human sentimentality that sticks out like a sore thumb.

In a movie about that abject stupidity of the human world, it feels a bit like someone is pulling the rug out from under us when Barbie willingly volunteers to leave Barbieland to become one of the subjugated. In my eyes, choosing the human world is not the synonym for gaining a soul that the film thinks it is.

Having said that, I want to quickly state that this is a rather nitpicky criticism, and that the vast majority of the movie is an incredible success. Gerwig’s direction of actors is impeccable, leading to career performances from Robbie, Gosling, as well as America Ferrera. To boot, the production design is stunning.

For about 85% of it’s run time, Barbie is exactly what I wanted. In a world where most movies are batting about .350 of their run time, I’d say that’s a victory. I thoroughly look forward to Ryan Gosling’s Best Supporting Actor acceptance speech.

Or, will Robert Downey Jr. have something to say about that?

That elegantly transitions us to Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer — a film based on the 700-page biography of father-of-the-A-bomb Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer subtly titled, American Prometheus.

If that doesn’t feel appropriately weighty, let me assure you that this film is Barbie’s polar opposite in every regard.

Any review of Oppenheimer worth its salt has to acknowledge the undeniable magnitude of its undertaking. Afterall, the stakes of any biopic are high: the filmmaker owes the audience a greater sense of truth and reverence. The larger the figure, the more scrupulous the audience.

As Nolan himself has claimed many times during his press tour, this is a film about arguably the single most important person who ever lived. Forever, Oppenheimer’s legacy will loom over every political decision from now until every nation decides to launch their own arsenal of his babies, and we finally return to dust.

Nolan hammers those stakes home and then some. Most impressively, the frantic pacing, maniacal score, and titanic performances render any criticism of the film’s nearly 3-hour run time a moot point.

Make no mistake, this is one of the most affecting, visceral films ever made. Nolan must be suitably applauded for being able to conjure that feeling in his audience when the film is mostly well-dressed scientists having discussions in a sparse room.

In fact, what I love about both of these films is that they make such virtuosic use of every production element. Barbie’s soundtrack makes the exposition of Barbieland (literally) sing, turning rules into jokes. Meanwhile, Oppenheimer’s immaculate sound design places us in Oppenheimer’s own internal world.

The stars of Barbie and Oppenheimer also both deliver on the promise of their casting. Just as Robbie is the perfect actor to fit the superficial Barbie bill, while suitably bringing pathos — Cillian Murphy manages to be simultaneously closed off, haunted, and effortlessly charismatic.

And yet it’s the internal logic of Oppenheimer the man, that I found prevented me from fully giving myself over to the movie.

Whether or not a director adheres to history like gospel in the making of a biopic, most authors have a distinct impression of their subject that they wish to express to their audience.

While considering Oppenheimer, my mind kept returning to another film about a more modern titan: David Fincher’s The Social Network. Contrary to Oppenheimer, that film offers a very specific, if not impressionistic explanation for Mark Zuckerberg’s drive.

The film both opens with the socially clueless Mark Zuckerberg getting dumped by his college girlfriend, and closes with him searching for her (and probably her relationship status) on his terrible new creation: the Facebook.

The impression Fincher and screenwriter Aaron Sorkin wish to leave us with? This is a stupid, socially inept kid, who happens to have a 180 IQ and the ability to manifest an entire organized data-based social hierarchy in order to attempt to understand why a girl doesn’t like him anymore.

Is this an accurate representation of the real Mark Zuckerberg? Probably not, but it’s a distinct take that drives home the incredible danger of a platform like Facebook.

I cannot decide if its to Oppenheimer’s benefit or detriment that the film does not have such a north star to guide it. Cillian Murphy’s Oppenheimer is much more complicated than Jesse Eisenberg’s Mark Zuckerberg. And yet, as the lead character of this film, in a vacuum — he is unknowable.

There can be no doubt that Oppenheimer was a man of contradictions. After the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Oppenheimer spent the rest of his life campaigning against the use of the bomb, and the development of the Hydrogen bomb. Yet he never apologized for their use in Japan. When the Manhattan project was commissioned, Oppenheimer — a Jewish man — was racing Hitler and the Nazi’s to get to the bomb first. Yet, when Hitler died and Germany surrendered, he insisted that the only way to ensure the end of all war was to use the weapon.

Even in his personal life, Oppenheimer was non-committal. He flirted with the communist party, and had numerous extra-marital affairs.

I believe that Nolan is intentionally emphasizing the nebulous nature of Oppenheimer’s life. But his best explanation seems to be… that there is none. And from a storytelling perspective, that’s rather frustrating.

The closest Nolan comes to arriving at a conclusion about Oppenheimer, is also the film’s greatest use of artistic license. The final scene of the movie depicts a conversation between Albert Einstein and Oppenheimer. The later had previously approached Einstein for his opinion on the slight issue of the A-bomb test potentially igniting the entire Earth’s atmosphere.

The test went as planned, and the rest is history. Now Oppenheimer is left with the burden of having created the most terrible weapon in the history of humanity.

He asks Einstein if he remembered when he thought that they might destroy the world. Einstein tells him he does, and Oppenheimer replies gravely: “I think we did.”

I won’t be watching Oppenheimer again any time soon. It’s a profoundly upsetting film, and I mean that in the most complimentary way possible. But I have a feeling something about it will always elude me, and maybe that’s the point.

In the end, neither Barbie nor Oppenheimer are perfect. But this weekend at the movies united people in a wonderful, albeit odd, way. I don’t think we’ll see anything like this again for some time.

That’s pretty special.